Una imagen de alta resolución de la Tierra tomada por el orbitador lunar japonés Kaguya en noviembre de 2007. Crédito: JAXA/NHK

Se está gestando una nueva era de exploración lunar, con docenas de misiones lunares planeadas para la próxima década. Europa está a la vanguardia aquí, contribuyendo a la construcción de la estación lunar Gateway y la nave espacial Orion, que están destinadas a devolver a los humanos a nuestro satélite natural, así como al desarrollo del gran módulo de aterrizaje lunar logístico, conocido como Argonaut. Dado que docenas de misiones operarán en y alrededor de la Luna y deberán comunicarse entre sí y fijar sus ubicaciones independientemente de la Tierra, esta nueva era requerirá su propio tiempo.

En consecuencia, las organizaciones espaciales comenzaron a pensar en cómo mantener el tiempo en la luna. Habiendo comenzado con una reunión en el Centro de Tecnología ESTEC de la Agencia Espacial Europea en los Países Bajos en noviembre pasado, la discusión es parte de un esfuerzo mayor para acordar algo en común.red lunaArquitectura que cubre los servicios de comunicación y navegación lunar.

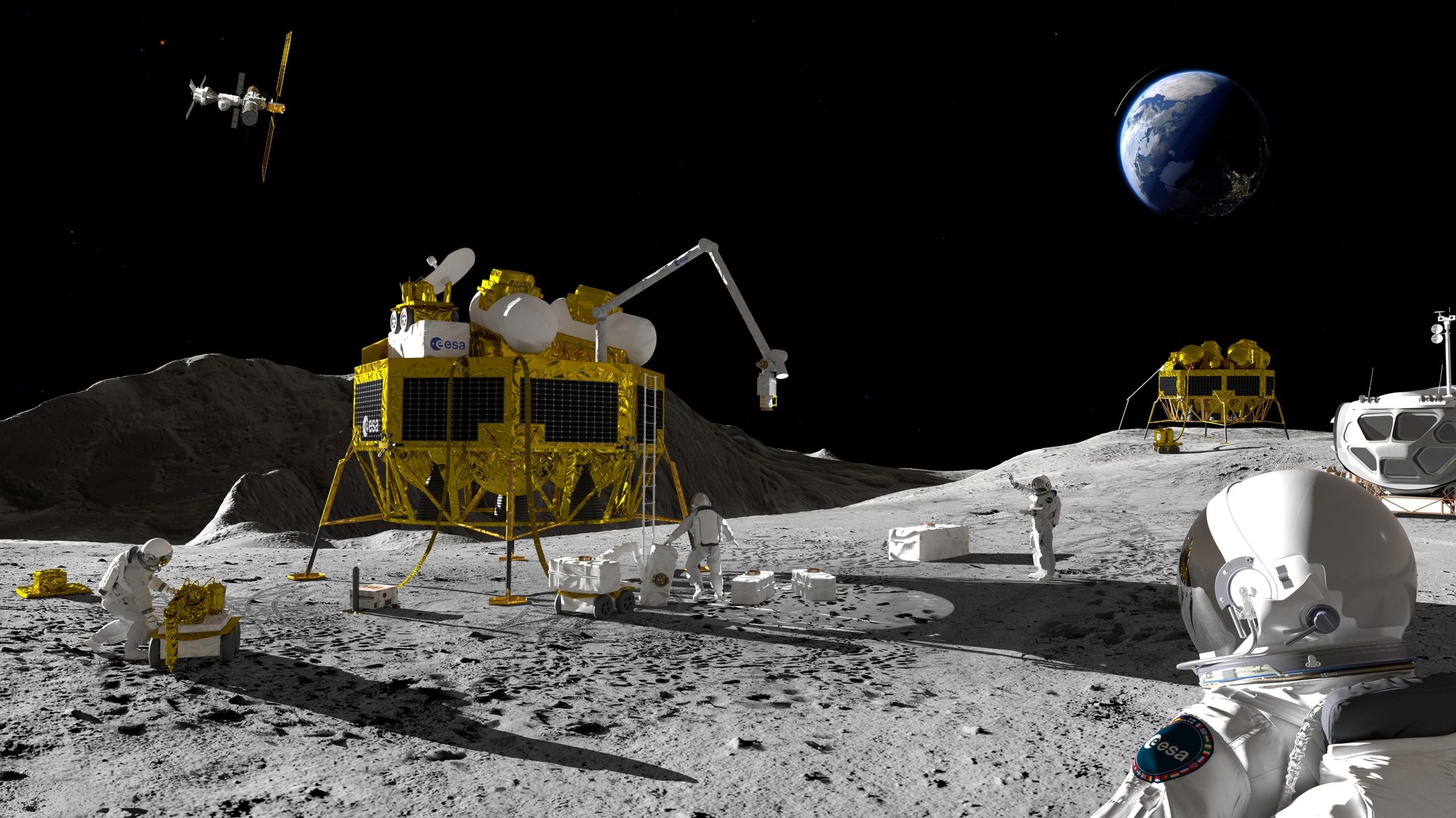

Impresión artística del escenario de exploración lunar. Crédito: ESA-ATG

Arquitectura para la Exploración Lunar Conjunta

“LunaNet es un marco de estándares, protocolos y requisitos de interfaz mutuamente acordados, que permite que futuras misiones lunares trabajen juntas, conceptualmente similar a lo que hicimos en la Tierra para uso común”.[{” attribute=””>GPS and Galileo,” explains Javier Ventura-Traveset, ESA’s Moonlight Navigation Manager, coordinating ESA contributions to LunaNet. “Now, in the lunar context, we have the opportunity to agree on our interoperability approach from the very beginning, before the systems are actually implemented.”

Timing is a crucial element, adds ESA navigation system engineer Pietro Giordano: “During this meeting at ESTEC, we agreed on the importance and urgency of defining a common lunar reference time, which is internationally accepted and towards which all lunar systems and users may refer to. A joint international effort is now being launched towards achieving this.”

On the 20th day of the Artemis I mission, Orion captures the Moon during its lunar flyby. The image was taken by a camera mounted on the European Service Module solar array wings, on December 5, 2022. Credit: NASA

Up until now, each new mission to the Moon is operated on its own timescale exported from Earth, with deep space antennas used to keep onboard chronometers synchronized with terrestrial time at the same time as they facilitate two-way communications. This way of working will not be sustainable however in the coming lunar environment.

Once complete, the Gateway station will be open to astronaut stays, resupplied through regular NASA Artemis launches, progressing to a human return to the lunar surface, culminating in a crewed base near the lunar south pole. Meanwhile, numerous uncrewed missions will also be in place – each Artemis mission alone will release numerous lunar CubeSats – and ESA will be putting down its Argonaut European Large Logistics Lander.

Artist’s impression of the lunar Gateway, a habitat, refueling, and research center for astronauts exploring our Moon as part of the Artemis program. Credit: NASA/Alberto Bertolin

These missions will not only be on or around the Moon at the same time, but they will often be interacting as well – potentially relaying communications for one another, performing joint observations or carrying out rendezvous operations.

Moonlight satellites on the way

“Looking ahead to lunar exploration of the future, ESA is developing through its Moonlight program a lunar communications and navigation service,” explains Wael-El Daly, system engineer for Moonlight. “This will allow missions to maintain links to and from Earth, and guide them on their way around the moon and on the surface, allowing them to focus on their core tasks. But also, Moonlight will need a shared common timescale in order to get missions linked up and to facilitate position fixes.”

ESA’s Moonlight initiative involves expanding satnav coverage and communication links to the Moon. The first stage involves demonstrating the use of current satnav signals around the Moon. This will be achieved with the Lunar Pathfinder satellite in 2024. The main challenge will be overcoming the limited geometry of satnav signals all coming from the same part of the sky, along with the low signal power. To overcome that limitation, the second stage, the core of the Moonlight system, will see dedicated lunar navigation satellites and lunar surface beacons providing additional ranging sources and extended coverage. Credit: ESA-K Oldenburg

And Moonlight will be joined in lunar orbit by an equivalent service sponsored by NASA – the Lunar Communications Relay and Navigation System. To maximize interoperability these two systems should employ the same timescale, along with the many other crewed and uncrewed missions they will support.

Fixing time to fix position

Jörg Hahn, ESA’s chief Galileo engineer and also advising on lunar time aspects comments: “Interoperability of time and geodetic reference frames has been successfully achieved here on Earth for Global Navigation Satellite Systems; all of today’s smartphones are able to make use of existing GNSS to compute a user position down to a meter or even decimeter level.

Picture of the far side of the Moon taken on flight day six of the Artemis I mission from the Orion spacecraft optical navigation camera. Credit: NASA

“The experience of this success can be re-used for the technical long-term lunar systems to come, even though stable timekeeping on the Moon will throw up its own unique challenges – such as taking into account the fact that time passes at a different rate there due to the Moon’s specific gravity and velocity effects.”

Setting global time

Accurate navigation demands rigorous timekeeping. This is because a satnav receiver determines its location by converting the times that multiple satellite signals take to reach it into measures of distance – multiplying time by the speed of light.

Your satnav receiver needs a minimum of four satellites in the sky, their onboard clocks synchronized and orbital positions monitored by global ground segments. It picks up signals from each satellite, which each incorporate a precise time stamp.

By calculating the length of time it takes for each signal to reach your receiver, the receiver builds up a three-dimensional picture of your position – longitude, latitude, and altitude – relative to the satellites. Future receivers will be able to track Galileo satellites in addition to US and Russian navigation satellites, providing meter-scale positioning accuracy almost anywhere on or even off Earth: satnav is also heavily used by satellites.

Credit: ESA

All the terrestrial satellite navigation systems, such as Europe’s Galileo or the United States’ GPS, run on their own distinct timing systems, but these possess fixed offsets relative to each other down to a few billionths of a second, and also to the UTC Universal Coordinated Time global standard.

The replacement for Greenwich Mean Time, UTC is part of all our daily lives: it is the timing used for Internet, banking, and aviation standards as well as precise scientific experiments, maintained by the Paris-based Bureau International de Poids et Mesures (BIPM).

Galileo is based on a worldwide time reference called Galileo System Time (GST), the standard for Europe’s satellite navigation system, kept close to UTC with an accuracy of 28 billionths of a second. Accurate timings enable accurate ranging for position and navigation services, and their dissemination is an important service in its own right. Credit: ESA

The BIPM computes UTC based on inputs from collections of atomic clocks maintained by institutions around the world, including ESA’s ESTEC technical center in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, and the ESOC mission control center in Darmstadt, Germany.

Designing lunar chronology

Among the current topics under debate is whether a single organization should similarly be responsible for setting and maintaining lunar time. And also, whether lunar time should be set on an independent basis on the Moon or kept synchronized with Earth.

A mosaic of the south pole of our Moon showing locations of major craters, with images taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

The international team working on the subject will face considerable technical issues. For example, clocks on the Moon run faster than their terrestrial equivalents – gaining around 56 microseconds or millionths of a second per day. Their exact rate depends on their position on the Moon, ticking differently on the lunar surface than from orbit.

“Of course, the agreed time system will also have to be practical for astronauts,” explains Bernhard Hufenbach, a member of the Moonlight Management Team from ESA’s Directorate of Human and Robotic Exploration. “This will be quite a challenge on a planetary surface where in the equatorial region each day is 29.5 days long, including freezing fortnight-long lunar nights, with the whole of Earth just a small blue circle in the dark sky. But having established a working time system for the Moon, we can go on to do the same for other planetary destinations.”

Finalmente, para trabajar en conjunto adecuadamente, la comunidad internacional también tendrá que conformarse con un “marco de referencia central” común, similar al papel que juega en la Tierra el Marco de Referencia Terrestre Internacional, que permite la medición consistente de distancias precisas entre puntos a través de nuestro planeta. Los marcos de referencia asignados adecuadamente son componentes esenciales de los sistemas GNSS actuales.

“A lo largo de la historia humana, la exploración ha sido en realidad un factor importante para mejorar el cronometraje geodésico y los modelos de referencia”, agrega Javier. “Definitivamente es un momento emocionante para hacer esto ahora para la Luna, y trabajar para definir una línea de tiempo acordada internacionalmente y una referencia de centralización común, que no solo garantizará la interoperabilidad entre los diferentes sistemas de navegación lunar, sino que también mejorará una gran cantidad de investigaciones. y oportunidades de aplicación en el espacio lunar”.

“Futuro ídolo adolescente. Explorador amigable. Alborotador. Especialista en música. Practicante ávido de las redes sociales. Solucionador de problemas”.

More Stories

Compensar el sueño los fines de semana puede reducir el riesgo de enfermedad cardíaca en una quinta parte: estudio | Cardiopatía

¿Cómo se hicieron los agujeros negros tan grandes y rápidos? La respuesta está en la oscuridad.

Una estudiante de la Universidad de Carolina del Norte se convertirá en la mujer más joven en cruzar las fronteras del espacio a bordo de Blue Origin