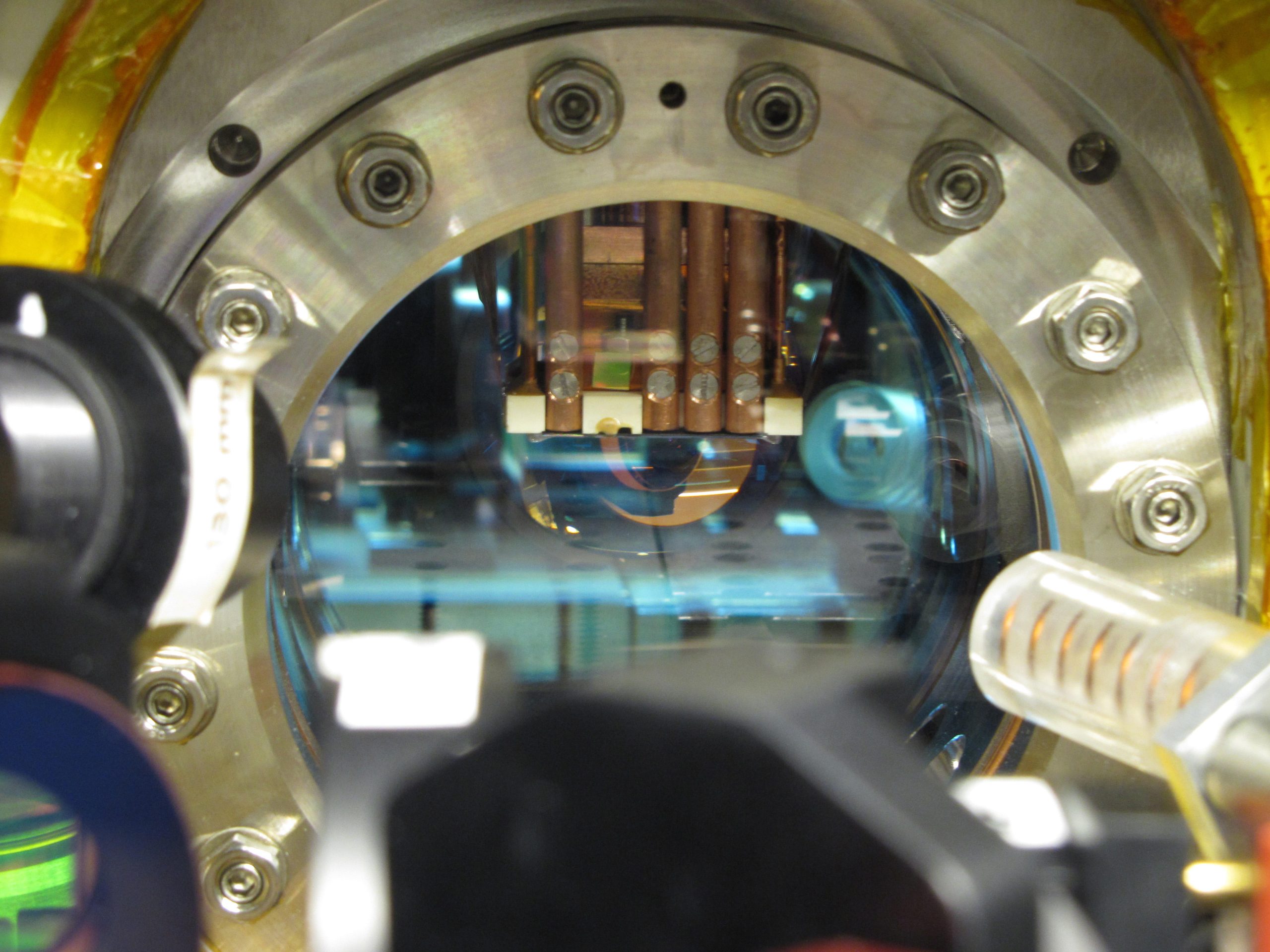

Cámara de vacío que contiene chips de maíz. Crédito: Thomas Schwegler, Universidad Técnica de Viena

¿Cómo intercambian información las partículas cuánticas? Una hipótesis interesante sobre la información cuántica fue validada recientemente por una validación experimental llevada a cabo en TU Wien.

Si tuviera que elegir al azar a un individuo de una multitud que es significativamente más alto que el promedio, es muy probable que esa persona también exceda el peso promedio. Esto se debe a que, estadísticamente hablando, el conocimiento sobre una variable a menudo nos da una idea de otra.

La física cuántica lleva estas conexiones a otro nivel, estableciendo vínculos más eficientes entre cantidades dispares: distintas partículas o partes de un vasto sistema cuántico pueden “compartir” una determinada cantidad de información. Esta intrigante hipótesis teórica sugiere que el cálculo de esta “información mutua” sorprendentemente no se ve afectado por el tamaño total del sistema, sino solo por su superficie.

Este sorprendente resultado fue confirmado experimentalmente en TU Wien y publicado en

“If the system is in equilibrium, then particles in different areas of the container know nothing about each other. One can consider them completely independent of each other. Therefore, one can say that the mutual information these two particles share is zero.”

In the quantum world, however, things are different: If particles behave quantumly, then it may happen that you can no longer consider them independently of each other. They are mathematically connected — you can’t meaningfully describe one particle without saying something about the other.

“For such cases, there has long been a prediction about the mutual information shared between different subsystems of a many-body quantum system,” explains Mohammadamin Tajik. “In such a quantum gas, the shared mutual information is larger than zero, and it does not depend on the size of the subsystems — but only on the outer bounding surface of the subsystem.”

This prediction seems intuitively strange: In the classical world, it is different. For example, the information contained in a book depends on its volume — not merely on the area of the book’s cover. In the quantum world, however, information is often closely linked to surface area.

Measurements with ultracold atoms

An international research team led by Prof. Jörg Schmiedmayer has now confirmed for the first time that the mutual information in a many body quantum system scales with the surface area rather than with the volume. For this purpose, they studied a cloud of ultracold atoms.

The particles were cooled to just above absolute zero temperature and held in place by an atom chip. At extremely low temperatures, the quantum properties of the particles become increasingly important.

The information spreads out more and more in the system, and the connection between the individual parts of the overall system becomes more and more significant. In this case, the system can be described with a quantum field theory.

“The experiment is very challenging,” says Jörg Schmiedmayer. “We need complete information about our quantum system, as best as quantum physics allows. For this, we have developed a special tomography technique. We get the information we need by perturbing the atoms just a bit and then observing the resulting dynamics. It’s like throwing a rock into a pond and then getting information about the state of the liquid and the pond from the consequent waves.”

As long as the system’s temperature does not reach absolute zero (which is impossible), this “shared information” has a limited range. In quantum physics, this is related to the “coherence length” — it indicates the distance to which particles quantumly behave similarly, and thereby know from each other.

“This also explains why shared information doesn’t matter in a classical gas,” says Mohammadamin Tajik. “In a classical many-body system, coherence disappears; you can say the particles no longer know anything about their neighboring particles.” The effect of temperature and coherence length on mutual information was also confirmed in the experiment.

Quantum information plays an essential role in many technical applications of quantum physics today. Thus, the experiment results are relevant to various research areas — from solid-state physics to the quantum physical study of gravity.

Reference: “Verification of the area law of mutual information in a quantum field simulator” by Mohammadamin Tajik, Ivan Kukuljan, Spyros Sotiriadis, Bernhard Rauer, Thomas Schweigler, Federica Cataldini, João Sabino, Frederik Møller, Philipp Schüttelkopf, Si-Cong Ji, Dries Sels, Eugene Demler and Jörg Schmiedmayer, 24 April 2023, Nature Physics.

DOI: 10.1038/s41567-023-02027-1

“Futuro ídolo adolescente. Explorador amigable. Alborotador. Especialista en música. Practicante ávido de las redes sociales. Solucionador de problemas”.

More Stories

Compensar el sueño los fines de semana puede reducir el riesgo de enfermedad cardíaca en una quinta parte: estudio | Cardiopatía

¿Cómo se hicieron los agujeros negros tan grandes y rápidos? La respuesta está en la oscuridad.

Una estudiante de la Universidad de Carolina del Norte se convertirá en la mujer más joven en cruzar las fronteras del espacio a bordo de Blue Origin